Robert Gersh

In 1975, when I was ten, my father got orders to move our family to West Germany. You see, my dad was an officer in the US Air Force and this was the much-coveted Tour of Europe for which he had long requested. But my family was Jewish and this was only 30 years after the end of World War II and the Holocaust. My Uncle Milton warned us that he would not visit us in Germany. He would only see us if we met him in France. I therefore wondered if it would it be okay. Would we have to hide that we were Jewish?

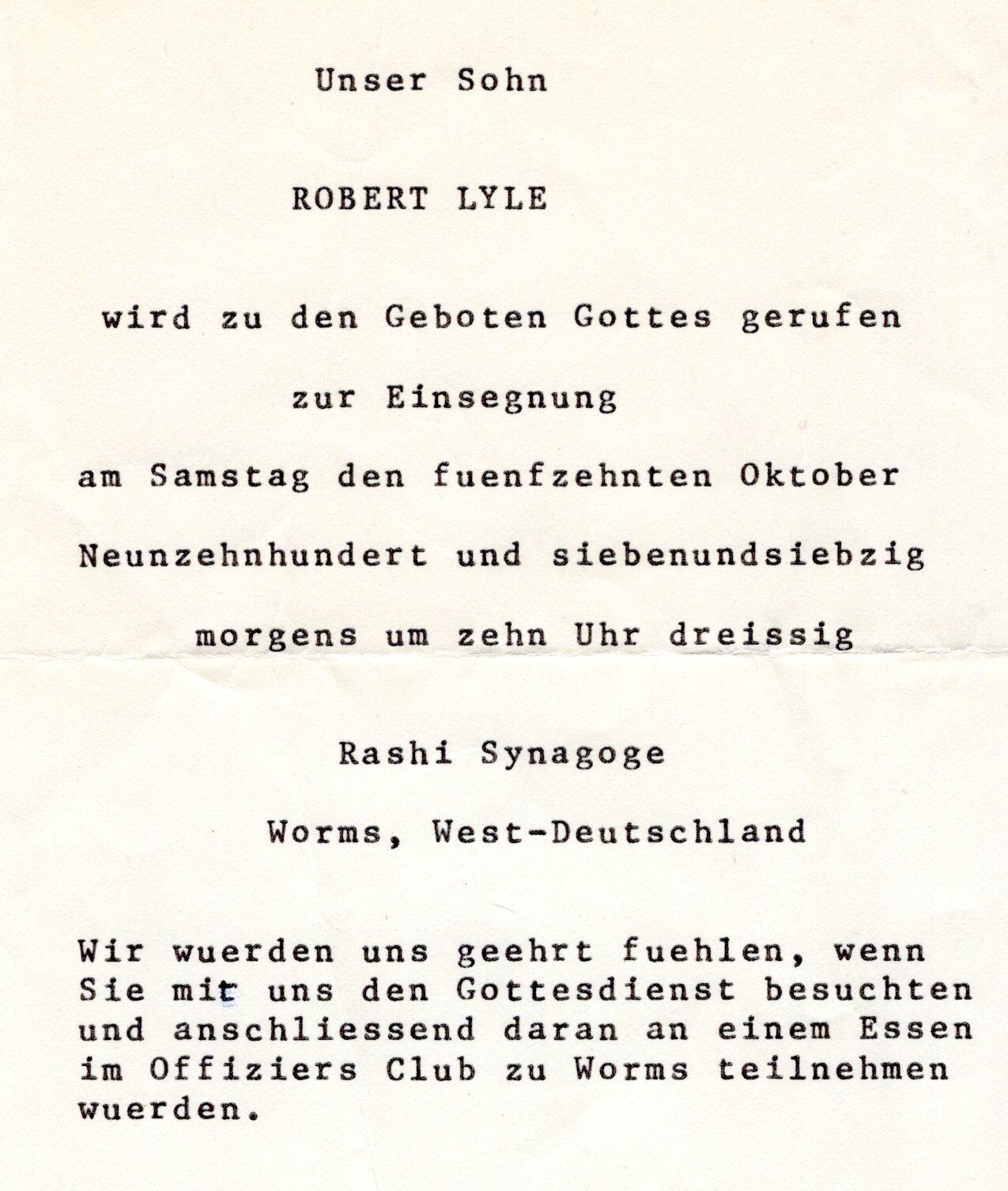

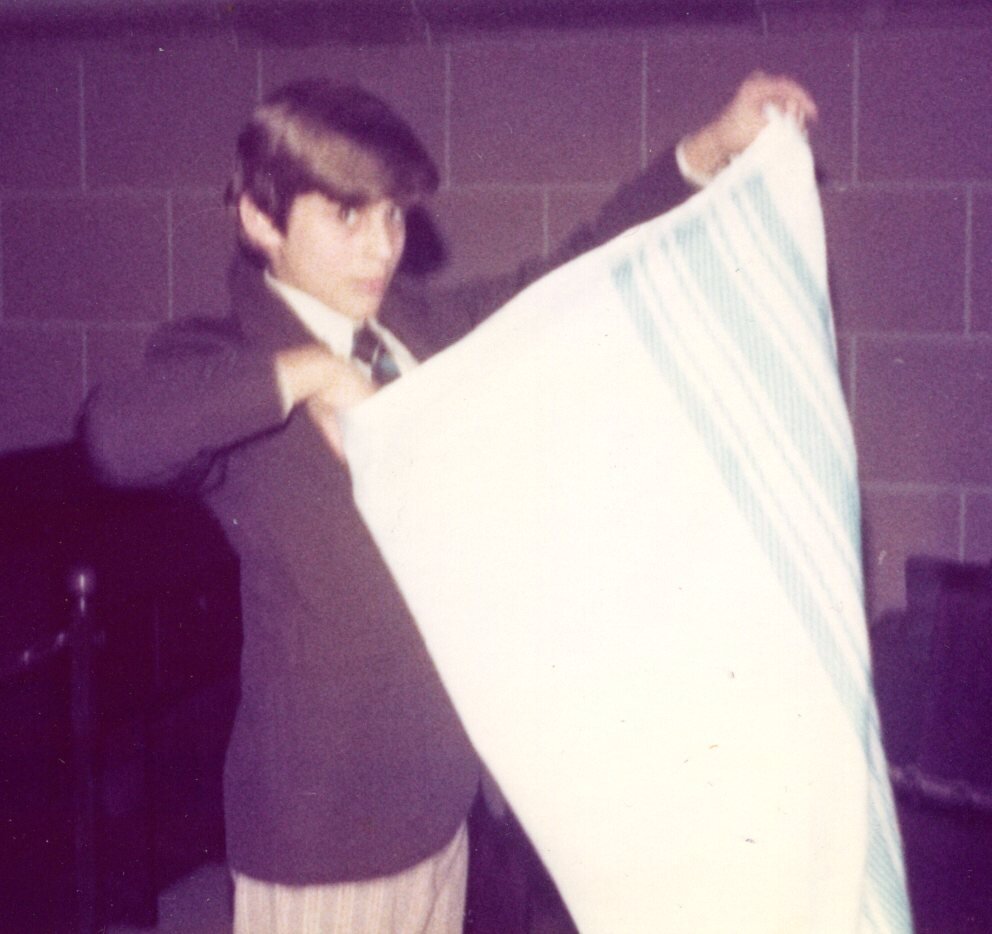

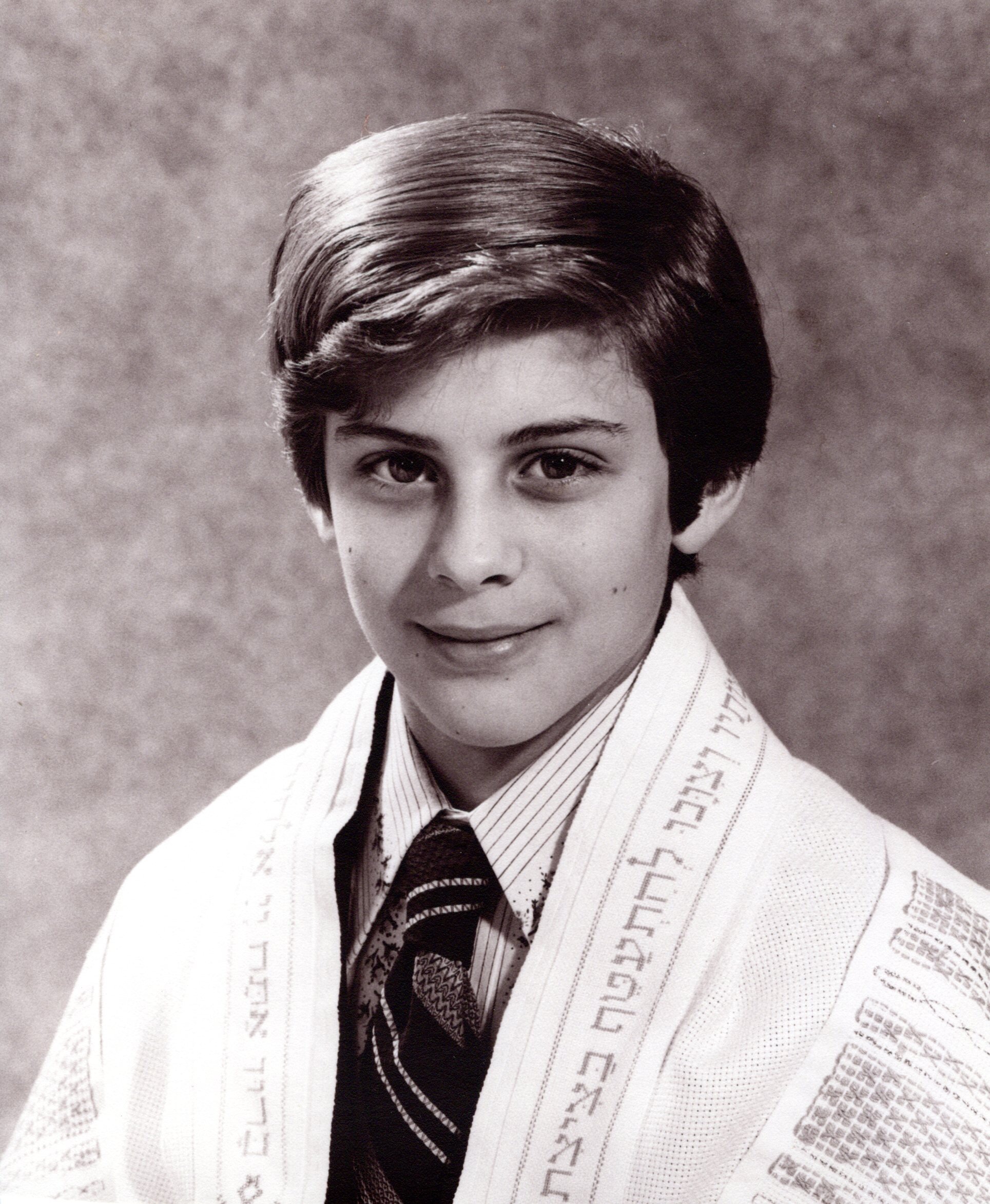

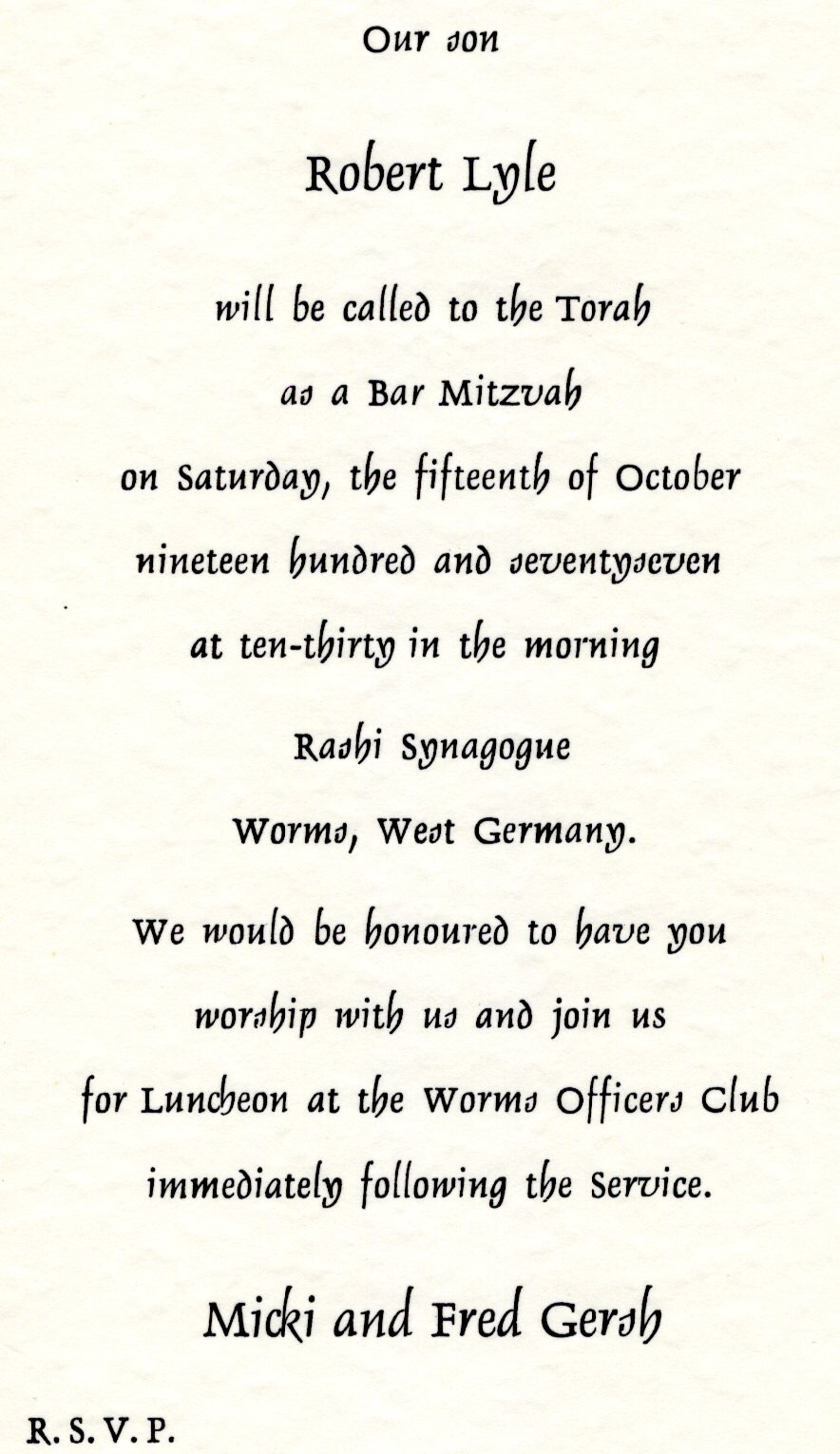

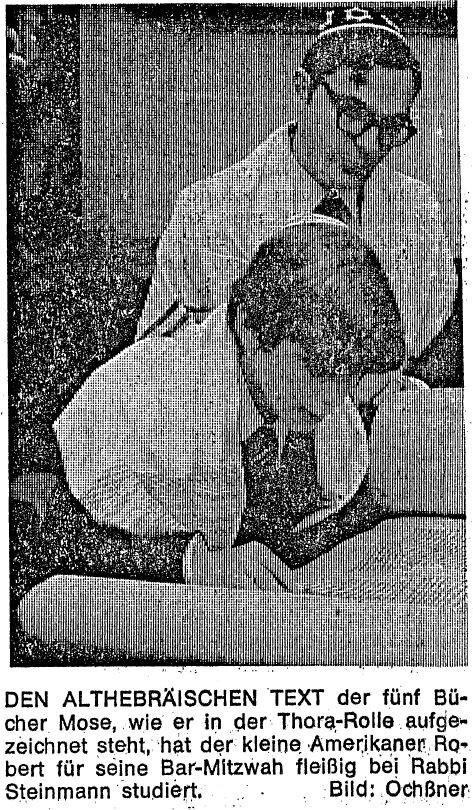

After we arrived at the Ramstein Air Force Base in Germany, we began to regularly attend the weekly Friday Night Shabbat services at the base chapel that was led by the assigned Air Force chaplain, Rabbi Irving Ehrlich and later Rabbi Theodore Stainman. Our congregation of service-members and their families was thriving and I continued my Jewish education in their religious school. Our congregation occasionally held services in the historic, eleventh century synagogue in the nearby city of Worms. It was sometimes called the Rashi Shul or Rashi Synagogue after the famous medieval French Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac, an acclaimed commentator on the Talmud and the Hebrew Bible, who had studied in the yeshiva there for many years until he moved to Mainz around 1065. Fortunately, my dad was able to get permission to hold my Bar Mitzvah ceremony at the Rashi Synagogue, which I did on Saturday, October 15, 1977. My mother hand made for me a lovely tallit and kippah that I wore for the occasion. It was my understanding that I was the first Bar Mitzvah held there since the synagogue had been rebuilt in the early 1960s. The local German newspaper, the Wormser Zeitung, even sent a reporter and a photographer to cover the event.

I was both nervous and excited the day of my Bar Mitzvah. I was nervous that I was going to make a mistake. But I was excited that I would finally get to demonstrate what I had learned. I am happy to say that my many hours of practicing paid off. My chanting from the Torah and Haftorah went really well. And my Bar Mitzvah speech comparing the “new beginnings” found within my Torah portion about the story of Noah and my Haftorah portion about the People of Israel’s exile to the land of Babylonia to my own “new beginnings” in my school, home, faith, and my greater community was well received.

Standing on the Bima and facing my rapt audience of family members, friends both German and American, and even journalists from the local newspaper, I knew that I was proud to be Jewish. I was carrying on the religious traditions of my ancestors in the very spot that had been destroyed during Kristallnacht in 1938. As it turns out, I did not have to hide my Jewishness to be accepted by the community. Instead, I got to celebrate it.